Sam Kolb’s Tape Deck

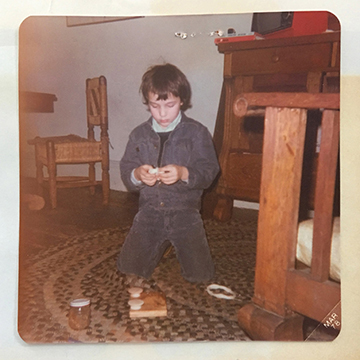

It is 1978. My best friend is David Satterthwaite. He lives next door to Sam Kolb, who is also our age but his family isn’t in the food co-op we’re in. We only play with Sam sometimes even though he lives right next door, but whenever we do it seems like he has a lot of toys. He has maybe eight times more Legos than me and he is the only kid I know who has a track for racing his Matchbox cars. And he has a portable tape deck. At my house we have a television with a red plastic case — which you can see on the dresser there — but we don’t have a stereo and I certainly don’t have my own tape deck. But I want a tape deck, so one night, on the floor of the dining room I make one, out of a piece of plywood, two wooden knobs, and some yarn. I am seven or eight years old.

Many years later, Sam Kolb will be the first person I ever see use a hashtag on Twitter. By then, I’m a graphic designer and even though I’m a working professional, in some fundamental way I’m still figuring out how to make tape decks out of wood.

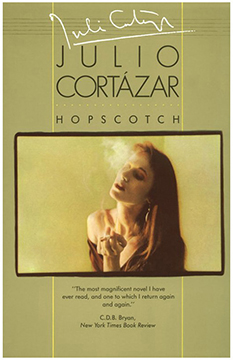

Paris, Hopscotch

It is July, 1990. The summer before my junior year in college. I’m on a week’s vacation in Paris, the result of an unlikely confluence of my sister and cousins also traveling in France and us somehow landing in a friend’s apartment for a week. My sister travels like my mother, which is to say she likes to keep moving and see everything and if there’s time move on to a new city or country. I am like my father: I want to sit in one place all day and read a book. Today my sister is at the train station seeing about trains to Madrid and I am sitting on a shady sidestreet drinking crème de menthe and Perrier and reading this novel, Hopscotch, to get ahead of the assignments for next semester.

As the book starts, the main character Horacio meets another character on the Rue du Cherche-Midi and I look up and I’m sitting at the corner of Rue du Cherche-Midi. And then, in the middle of chapter one, I find this sentence:

“But suddenly Harold Lloyd would go by and then you would shake off the water of your dream and finally be convinced that all was well, and that Pabst, and that Fritz Lang.”

I had no idea a sentence could work like this. This odd awkward sentence somehow feels right to me, in a way I can’t explain then or now. I write it down in my notebook.

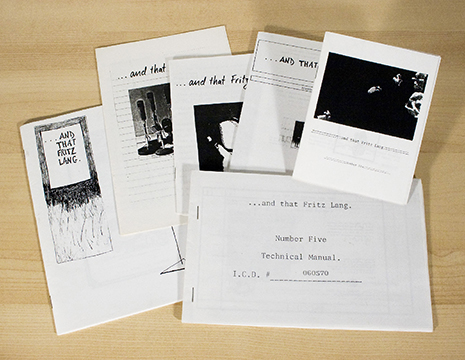

It is a nearly straight line, spread over the next seven or so years, from this sentence to me becoming a designer. During the fall of my junior year, I make the first issue of a zine titled “. . . and that Fritz Lang.”

In the spring I make another issue in a different format and with a Note on the Type, which is fictional. The Note on the Type becomes a tradition.

At this point, the only typefaces I know are the city fonts on the Mac.

The content is largely bits of writing and images torn from magazines. I use rubber cement, Wite-Out, a stapler.

The craftsmanship is rough because I know nothing about making things, but I love to figure out the form of each issue. It’s serious and personal work to me, making these scraps and fragments into something meaningful. Much of it only makes sense to me, but even that takes patience and persistence.

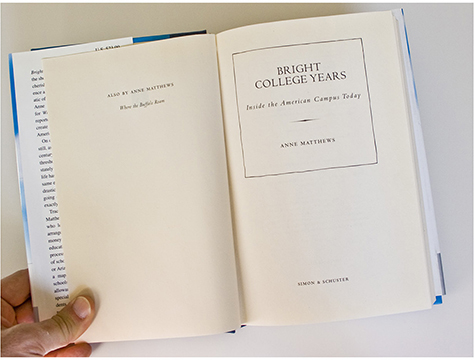

In 1995, I interview to be the assistant in the design department at Simon & Schuster. I’d been a literature major and a college textbook editor. The only thing I’ve ever designed, the only qualification I have to be in a design department anywhere, are these issues of . . . and that Fritz Lang.

Miraculously, the zines are qualification enough. Amy Hill hires me. She is an amazing mentor. I do admin tasks but after a couple months she has me design copyright pages for books going from hardcover to paperback. I learn to figure out which typeface is used in a book so that I can match it on the copyright page. I read Anthony Lawson’s Anatomy of Type. I read Fournier’s Manual on Typefounding. It’s not long before I just know which typefaces most books are set in. After a year in the job, Amy gives me a book to design, and without knowing that it’s happening, without seeing the hopscotch from a Paris afternoon to a xeroxed zine to this title page, I am a designer.

In my spare time I disassemble matchbooks and reassemble them with my own designs, carefully scoring each fold and gluing the scratchy bit down. I make hundreds of these.

The SPI Years

On June 10, 2002, I file a Certificate of Incorporation with state of New York and create an S corporation. Sam Potts Inc. is a legal business entity with all the attendant rights thereupon. It’s summertime again.

I have three clients to start with. After working at Simon & Schuster for three years, plus two years of design school at Portfolio Center in Atlanta and two years working for Eric Baker’s studio in New York, I set out as an independent graphic designer. For one of my first clients, I design matchboxes. Real matchboxes.

I’ve learned too much to make zines the way I used to, but I find the pleasure translates. I’m still figuring out how to make things. The job now is to make things that are meaningful for everyone.

I design for print and the web. It’s the early to mid aughts, so it’s still possible for one person to design and code a website. I like having a variety of projects, and at the same time I wonder if I’m missing out on bigger projects by not specializing. I end up never specializing. I remain small. At first I work from home, then in a shared office, then in a small office by myself off Union Square. I do all the work myself.

The first years go by so fast. Overall I’m phenomenally lucky. I have good clients who pay on time and am able to find a balance between delivering what they expect and making what feels right to me. I do all the work myself. I’m deepening my craft. The work I do feels personal, in that what I’m making for clients nevertheless has some connection to the person I am. My work for the most part feels of me, and this is the greatest luck of all.

Is this place real?

One day in 2003, I run into Scott Seeley in Park Slope. Scott’s the manager of the McSweeney’s store on Seventh Avenue. McSweeney’s is still a very big deal at this time. Scott tells me they’re closing the store and opening an 826.

An 826 means a tutoring center like the one Dave Eggers opened in San Francisco. That center has a pirate supply store in the front, with workspaces in the back. It’s a famous and quasi mythical thing in 2003. Scott says the Brooklyn version is going to have a superhero store in the front. I don’t know anything about superheroes, but I’m a big McSweeney’s fan and offer to help, maybe teach a zine workshop once they open.

A couple months later I email Scott to check in and see if they need any help. He says they’ve asked Chip Kidd to design the storefront, but it’s fallen through. I go ahead and design a few mockups of an awning. Eggers emails back and says they all look like yuppie Park Slope coffee shops. Which is fair.

“It needs to look amateur,” he says, “like someone with no design sense designed it. Like a hardware store.”

That single idea, that it’s a hardware store for superheroes, is the basis for everything we make. I start over with the storefront, looking at local auto body shops, refrigerator repair shops, the covers of early McSweeney’s, and local bodegas that put their phone number on the sign. I write jokes. I mix up five sans serifs, which a professional graphic designer should not do.

I send the new design over to Eggers.

“Perfect,” he says. “Can you design a store?”

A few months later the store opens. The floors are still bare plywood, but the cape tester is built and some posters are up and the storefront is drawing a lot of puzzled looks. David Byrne plays at the opening party. As we stand on the sidewalk drinking beer on a warm fall evening, my friend Jonathan calls it the biggest matchbox ever.

Learning to Synthesize Learnings

It is summer again, 2011. I’m starting a new job in the New York office of IDEO. Two remarkable things happen during my first month.

One, on a routine check-in call with the client, the owner of the company — scion of the family business — says to our team, quote, “It sounds like you don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.” I’ve never heard a client swear before. It’s very alarming.

Two, our team sleeps over in a bed store on Broome Street, for research. I sleep on a bed that costs $30,000 and wake up to people peering through the storefront as they walk to work.

I’ve come to IDEO to try to broaden the kind of design I do. I am looking for a new craft. At IDEO we talk about craft a lot. We talk about making, a lot. I’ve made a lot of things, seen my work in books and magazines and stores and even on TV. But at IDEO it feels like we spend all day talking. It feels like we think out loud all day.

After that first bed project, I work on a prototype retirement product for T Rowe Price, a speculative brand signature for Loews hotels, a set of tools around paying for college for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and a speculative brand platform around quantified self for Weight Watchers. There is a new methodology to learn, and lots of new forms of collaboration, which is very new for me. There is a lot of jargon. I start to change as a designer. I start to absorb the human-centered approach. I learn about human factors and synthesis. I write How Might We’s. I develop strong preferences about Sharpies.

In fairness I learn a great deal. I learn to design for the user, and truth be told this is new for me. I have previously designed for the client, to deliver something that met their needs and expectations. I learn to work lo-res, at a sketch level so that ideas can be killed without much loss. This is extremely liberating. I learn not to accept the assumptions of the brief. I learn that the doing of the project can itself be creative, that you have to design the project. I become less concerned with form and more with structure and use.

I become a different kind of designer but I never become a true believer. IDEO projects are speculative blue-sky work and this kind of work is not dependent on form. It’s not an extension of craft as I’ve always known it. I come to realize that the work we do doesn’t feel connected to the person I am. It never stops being strange for me. I miss the zines and the matchbooks.

Coda: Tools

I start buying tools. I have worked as a graphic designer, I’ve tried strategy & innovation consulting, I’ve tried to think more broadly. It’s been hard to get back to the pleasure of just figuring out how to make things.

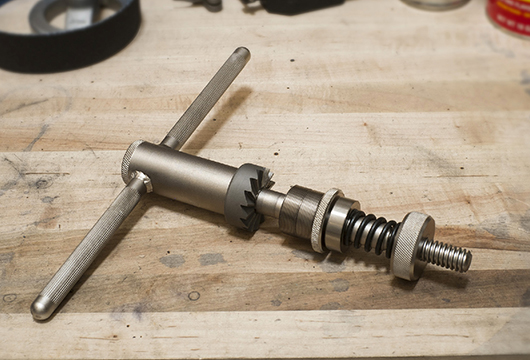

So I start buying tools. Very specific specialized tools that do very specific things. Tools like this:

And this, which looks pretty similar to the other one but is for something completely different:

This tool is a bottom bracket facing tool. It weighs about 4 pounds. The weight is important because you feel it when you pick it up. The weight is its presence in your hand. Unlike all of the digital tools we now quote unquote build with, the experience of this tool is physical. It commands you to be present.

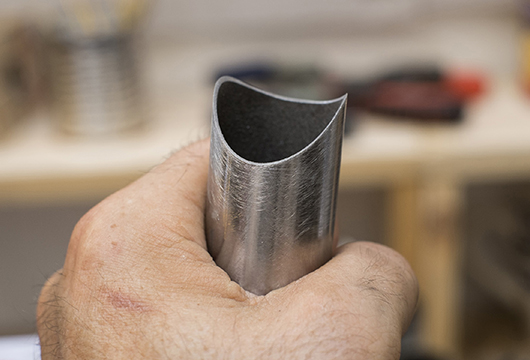

A bottom bracket facing tool does one thing. It faces a bottom bracket. To face something is to square off its opposing sides so that the surfaces are perfectly flat and perfectly parallel. This is a bottom bracket.

And this is how you might be more familiar with it. It’s the part of a bicycle frame where the crank axle runs through the frame. The bottom bracket holds the axle stable so that you can pedal in smooth circles. If the bottom bracket is not correctly faced, you’ll end up pedaling crosswise to the vertical plane of the bike. If this happens, you’ll know it because you just crashed.

This bottom bracket is on a bicycle that I made at the Yamaguchi Framebuilding School in Rifle Colorado.

This is my framebuilding teacher, Koichi Yamaguchi.

Koichi has been building bicycle frames by hand all his life. He has built bikes that have set world records, won world championships, been ridden by the US Olympic team. Koichi is a master craftsman. His hands are geniuses.

My hands have a lot to learn about building bike frames. For example — this is me working on mitering a tube.

Mitering is one of the most important steps in building a frame. This is what a mitered tube looks like — it’s kind of a fish-mouth shape.

The fish mouth fits around an abutting tube like this to form a snug joint.

You can do a miter on a drill press or a lathe in about a minute, 99% of which is set up time. In Koichi’s class, we do all the mitering by hand. With a file. Doing it by hand, when you’re a beginner, takes about 15 minutes, and 80% of that time is getting the last couple millimeters to be properly shaped all the way around.

To begin, you set your tube in the vise at the angle it will be on the bicycle.

You stand square to the workbench and you hold your file level as you push it across the end of the tube. Stroke by stroke. After a few minutes of filing, the miter shape starts to form. At first it’s shallow and as you file it takes on a deeper curve.

You’ll have drawn a line with a Sharpie to guide you. This line is important because your tube has to be the exact right length for everything to fit together. You work slowly and deliberately, paying attention to each file stroke.

Pretty soon, maybe sooner than you expect, you start getting close to the Sharpie line, so you put a short piece of tube into the joint to check the angles. Then you go back and file off a bit more.

Once you think you’ve got it, you take the tube out of the vise and clean it off with some sandpaper and show it to Koichi. The edges gleam silver and are very sharp. Koichi peers over his glasses at your work. “This part,” he says, pointing to an edge. “This part is a little bit struggling.”

It isn’t right. You knew this. You didn’t want to admit it but you did. You’ve been doing this for only a few days but you’ve already picked up what a proper miter should be. You know you need to be patient and keep trying but you don’t actually have any experience with this particular form of patience. After years of working on the computer, you’re unused to asking your hands to do something they can’t do. You’re unused seeing your hands produce a result that doesn’t equal the image in your mind. Basically, you suck at this.

“Yes, Koichi,” you say and go put the tube back in the vise for like the 18th time. You know you have to be careful about filing off too much. Your hands, by the way, will be blackened and rough and smell like steel.

You take a deep breath. You focus on the tube, clearing your head of all other thoughts. You take the file in your hand and try again.

Three strokes. Four. As level and straight as you can. A fifth stroke. Okay clean it off. Test it again. Koichi comes over.

“I don’t know,” you say, trying to convey that you know it’s still not right and you’re not a quitter but also you might be just about to whack this fucking tube with your file.

“Okay,” Koichi says and takes the file from you. He takes a look, peering over his glasses. He lays the file down against the tube in the vise and — stroke — stroke — stroke — and I swear to god it’s perfect. It’s wonderful. Gratitude washes over you, a gratitude all out of proportion to this small detail among so many on the bike you’re building. A detail that will in fact be unseen, hidden inside the frame, when the bike is finished.

The subtlety of his skill is nearly incomprehensible to you, except that he just did it right in front of you. It’s a profound thing to witness this. To see a difficult job done with what called only be called grace. And it’s a humbling thing, to be a beginner again and see, in Koichi’s handiwork, the patience and persistence that craftsmanship requires.

You remember that you’re the kind of designer for whom the thing you make is a connection to the person you are. You are seven or eight years old, you’re just finishing school, you’re starting out on your own, you’re trying to reinvent yourself. You look now across the room and your bike is leaning against the wall. It’s almost summertime. You should go out for a ride.